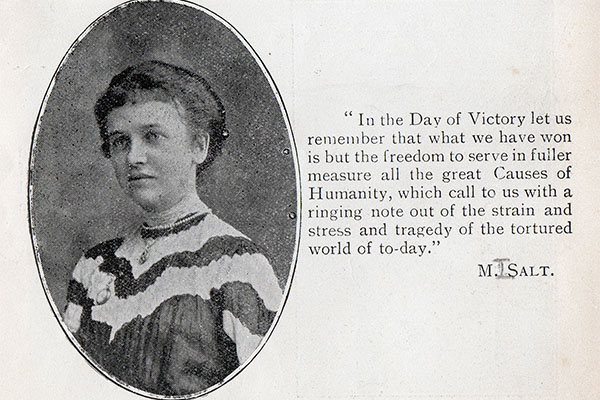

Isabel made sure that the work which women were doing was kept in the public eye, and war or no war she continued to advocate equal pay. The Shipley Times and Express for 21 April 1915 carried an account of a speech, Woman’s work in war time, where Isabel ranges over the effect of war on social questions

private interests must be sunk for the public good”. There must be a change in attitude to employment of women as drivers, interpreters, doctors, who did not get equal pay.

Chauffeurs belonging to the Red Cross Society are receiving better salaries than highly skilled and highly trained nurses” (Shame). There must be “Equal pay with men for equal work

This theme of opportunity for women in war is continued in various speeches:

The great lesson of the war was that they [women] must gain more control over their destinies.

(Shipley Times and Express, 9 Nov 1917)

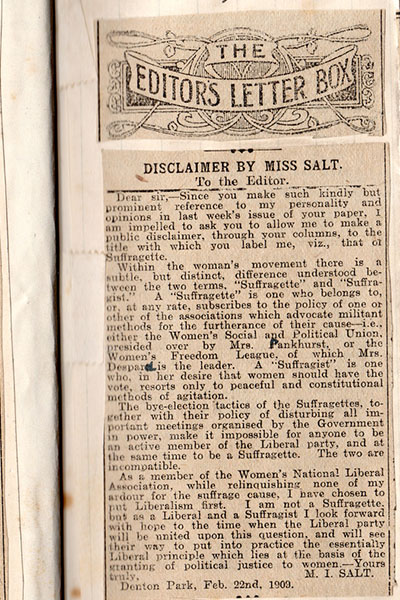

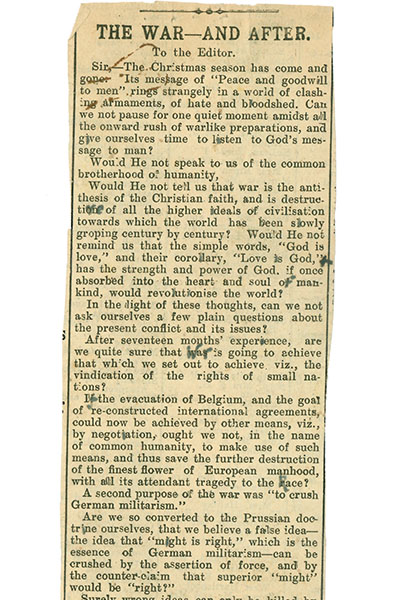

The fact that she knew that if women seized the opportunities presented by the war, it would bring votes for women nearer did not blind her to the futility of war and the dangers of militarism and the arms race. In her letter, The war and after, which she sent to the Harrogate and Claro Times in December 1915, under the name, Candida, she pleads that the war has been going on for 17 months, and has achieved nothing but destruction and misery. It is nonsensical to try to crush Prussian militarism by the same tactics. Only a change of heart can achieve what is needed.

Isabel and her mother had moved from Denton Hall in 1911 to Thorpe Arch near Boston Spa, so the Harrogate and Claro Times was their local paper. She could still go back to Saltaire to give talks, as one at the Saltaire Institute, recorded in the Shipley Times and Express 23 April 1915, where she describes war as “a cause of hatred, envy, fear, selfishness and greed.”

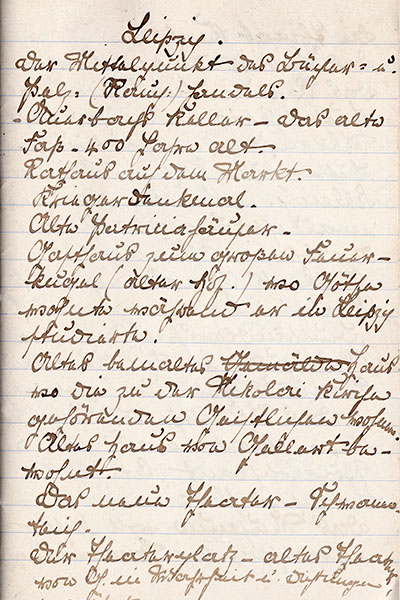

Isabel had become a member of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, by 1918. They favoured conciliation and were opposed to violence. Another possible reason for her desire to spare Germany suffering was her friendship with the German family she had visited before the war. Her passport shows she continued to visit Germany, and possibly this same family, in 1921 and 1922.