Innovator, industrialist,

politician,

philanthropist

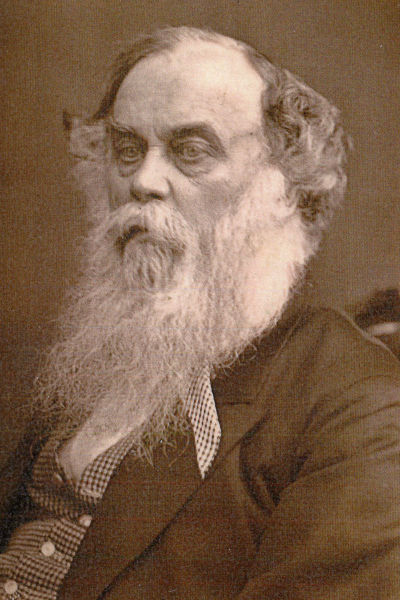

Sir Titus Salt was a leading Bradford mill owner and philanthropist of the nineteenth century.

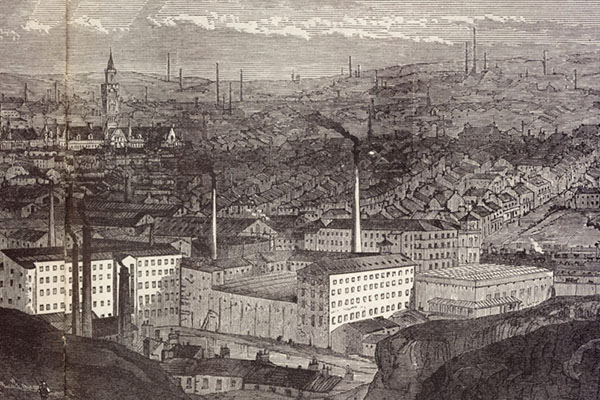

In the 1850s he moved his textile business out of overcrowded Bradford and built Salts Mill and the surrounding model village of Saltaire.

Here you can read about his early life, his business success in the growing textile industry of the nineteenth century, and the business, social, moral and religious reasons for his creating the model village of Saltaire.

Early life and education

Titus Salt was born in 1803. He was initially educated in a ‘dame school’ in Morley (near Leeds), then at Batley Grammar School and later given a commercial education at a Wakefield school. He was described as tall, stout, with a heavy appearance and as having a studious turn of mind – rarely mixing with his school fellows and being somewhat introverted.

He was known to have some difficulty in reaching decisions and was perceived to be unable to speak confidently or coherently in public. He had a highly developed sense of responsibility however and this offset his diffidence.

A start in business

In 1820 Titus was apprenticed to a wool stapler, a Mr Jackson of Wakefield. When the family moved to Bradford, he spent two years with William Rouse and Son where he gained a more comprehensive insight into the textile business.

In 1824 he joined his father’s business and the firm was renamed Daniel Salt and Son. Titus worked in the family firm for ten years and the firm began to specialize in Donskoi wools from Eastern Europe.

A Congregationalist in religion, he took part in public life alongside his father and was also a committed liberal-radical in his politics.

Marriage and parenthood

In 1830 Titus married Caroline Whitlam of Grimsby, the youngest daughter of Mr. George Whitlam who was a wealthy sheep farmer.

He first took a house in North Parade, Bradford, very near to his parents’ house but between 1836 and 1843 he lived at the junction of Thornton Road and Little Horton Lane. This was very near Nelson Court and Fawcett Court, the heart of a deprived area in Bradford. His understanding of and concern for the deprivation of many families may well have developed here.

Titus’s eldest children spent their early years living very close to this part of town. Of his surviving children, William Henry was born in 1831; George in 1833; Amelia, 1835; Edward, 1837; Herbert, 1840; Fanny, 1841; and Titus Junior, 1843.

Starting his own business

Titus and his father had started a spinning department at their wool stapling business, using rooms in Thompson’s Mill at Goitside Thornton Road, Bradford. They had been joined in the business by Titus’s brother Edward in 1834 and shortly after this Daniel Salt retired. Within a few months Titus had also left the firm and started to work on his own account. The family partnership was dissolved in 1835.

Titus started his new venture at Hollings Mill and quickly acquired premises on or near Hope Street in Bradford. In 1836 he took over a large mill in Union Street, whose previous owner had been Daniel Illingworth, and this became the headquarters of his rapidly expanding Alpaca manufacturing.

Alpaca and innovation

Alpaca wool became known in the United Kingdom in the early years of the nineteenth century when new trading connections were being developed with Latin America.

Although several amateur innovators experimented with the new material it was not until the 1830s that its commercial properties were tested. Early trials in worsted manufacture with this material were problematic. The first attempts to produce cloth with it, by Benjamin Outram of Halifax, involved very high costs and the finished cloth lacked lustre.

Following his experience with Donskoi wool, Titus Salt had the persistence and ingenuity to resolve the problems with Alpaca. Salt’s day book, kept between 1834 and 1837, includes notes which recorded costs of the material and its processing as he experimented. His trials with Alpaca weft and cotton warp proved successful, with records of early sales of the new cloth in 1839.

Salt was the only spinner of Alpaca weft in Bradford. He had worked in great secrecy for 18 months with trusted assistants and the cloth he produced in this way was durable, relatively light, lustrous and reasonably priced. Alpaca played a significant part in his success in textile manufacture.

Public service

The wealth which his business provided supported his very active public career and at one time or another he occupied almost every local public office.

He was elected High Constable of the Manor in 1841-42, organising and presiding at all town meetings requisitioned by the required number of rate payers. From 1847 to 1854 he was the senior alderman in the new Bradford Corporation for South Ward. In 1848-49 he was elected Mayor of the town and presided at almost all full council meetings.

Salt also sat regularly on the bench of the Bradford Court and was an active member of the Chamber of Commerce.

He became a member of parliament in in 1859 and remained in parliament for two years. He found parliamentary life something of a burden and in 1861 resigned his seat.

Later in 1874 Salt’s major contributions to public life was recognised by the erection of a statue in a prominent position outside Bradford Town Hall. It can now be seen in Lister Park, Bradford.

Business success

By 1843 Salt was enormously successful in business and had become very wealthy.

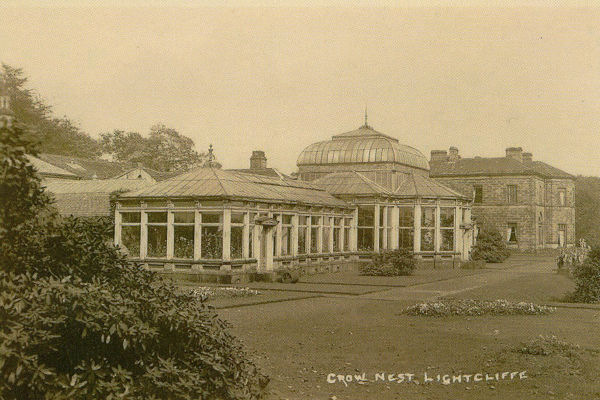

He ceased to live in Bradford moving with his family to a handsome mansion called Crow Nest at Lightcliffe (near Halifax, owned by the Walker family and once the home of Ann Walker), ten miles away from his business and his public commitments.

By this point in time there were several Bradford textile manufacturers who, by any standards, were wealthy men. Some joined the ranks of the aristocracy and titled gentry and a number confirmed their success in industry by converting their resources into landed estates.

For example, Samuel Cunliffe Lister bought the Masham and Jervaulx estates in North Yorkshire and some years later became Lord Masham. Mathew Thompson bought an estate in Kent, John Wood had many acres in Hampshire and George Hodgson, the textile engineer, bought an estate in Norfolk.

Founding Saltaire

Unlike many of his peers, Salt chose not to convert his fortune into a landed estate. Instead he created what was to become his memorial to the future by building the industrial community of Saltaire. Why he should choose to do this has never been definitively answered.

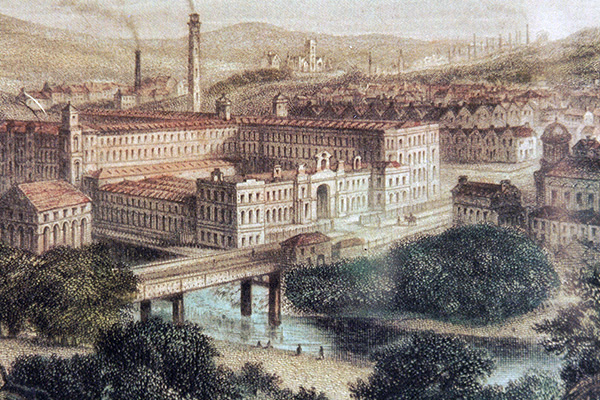

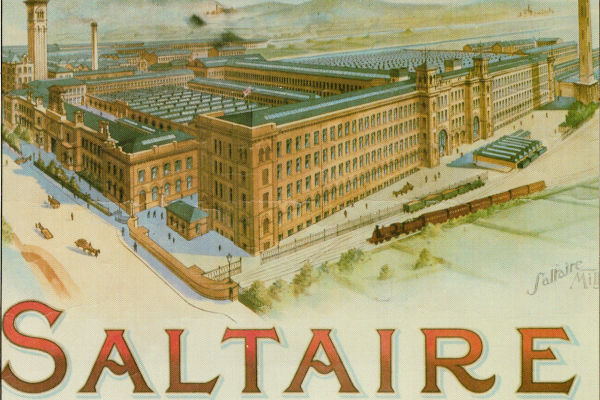

The site he chose for his new mill was four miles away from Bradford in a rural area on the banks of the river Aire at Shipley. The site stood between the river and the Midland Railway line and through its centre ran the Leeds/Liverpool canal. This crossroads of the principal lines of communication, north/south and east/west ensured cheap transport for coal, raw materials and finished goods.

Building Saltaire

Titus set out to build a grand ‘vertical mill’ – one that could take the raw materials in to the factory and have the machinery and capacity to perform the many processes required to complete and finish cloth of high quality.

He commissioned the architects Lockwood and Mawson to design the mill and settled on a fifteenth century renaissance style. William Fairbairn, a great engineer of the day, designed the layout of the interior and constructed the engineering facilities. The building of the mill commenced in 1851 and was completed in 1853. It had a production capacity for 30,000 yards of cloth every working day and employment at full capacity for 3,000 people.

Titus began the arrangements for building his industrial community of Saltaire as soon as the mill was completed. In October 1853, tenders were invited for the first 53 ‘cottages’ and by October 1854 14 shops were ready for occupation, 163 houses and boarding houses had been completed and around 1,000 people were in residence. By 1871 Saltaire already had a population of 4,390.

Salt ensured that the residents were provided with a range of public buildings and amenities including: a Congregationalist Church (now Grade I listed), schools, an educational and social institute, a hospital, almshouses, and a park.

Final years

After 1861, Titus lived in semi-retirement, relinquishing much of the day-to-day control of his mill and Saltaire to his business partners.

Titus had to leave Crow Nest in 1858 and moved to Methley Hall near Leeds. He managed to buy Crow Nest in 1868 and the family moved back to what they had come to regard as their family home.

Titus died on December 29, 1876. The legend of his charity, compassion and business acumen had spread long before his death, throughout the United Kingdom and far beyond its shores, where his name and the manufactured cloth associated with it was known and appreciated.

His funeral procession from Crow Nest to his final resting place in the mausoleum at Saltaire’s Congregational Church was to take many hours, most mills were silent, and many workers lined the streets to see his funeral carriage passing. The numbers assembling were estimated at around 100,000.

You may also be interested in

Explore our Collection for Titus Salt

Search and browse items from our Collection connected with Sir Titus Salt

The foundation of Saltaire

Read in more detail how the site for Saltaire was chosen and the mill, houses and public buildings developed

Saltaire's public buildings

Find out about the main public buildings and amenities built in Saltaire

More biographies and memoirs

Discover the life stories of some of the people who built, worked in, lived in, and saved Saltaire