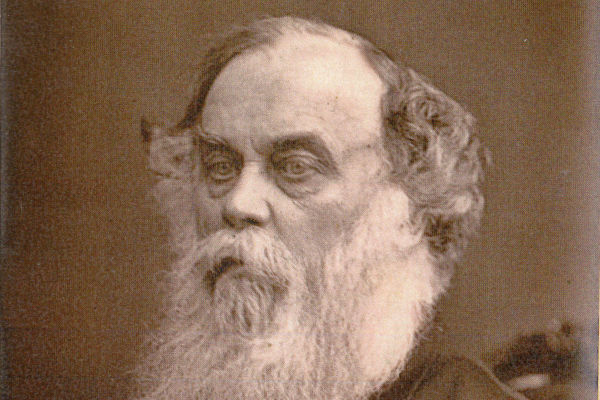

Titus Salt builds his mill and model village

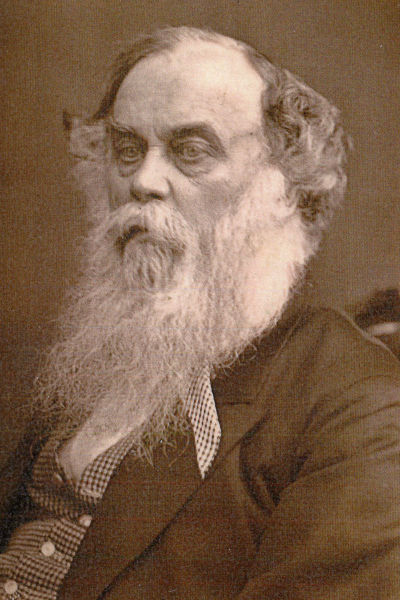

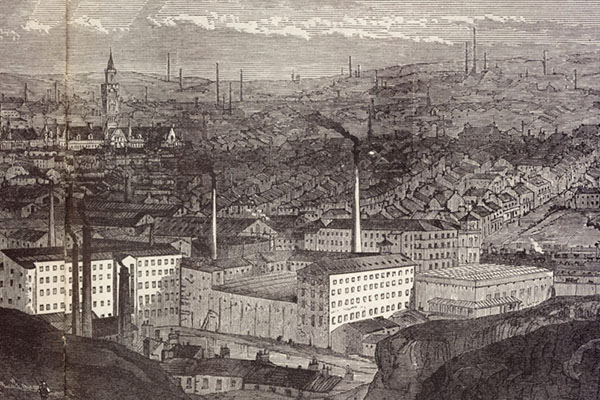

During the early nineteenth century Titus Salt achieved great success in the textiles industry in the growing Yorkshire town of Bradford. By the middle of the century Bradford had become hugely overcrowded and insanitary.

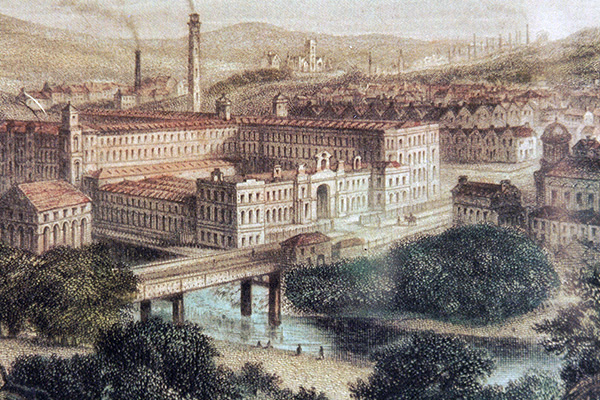

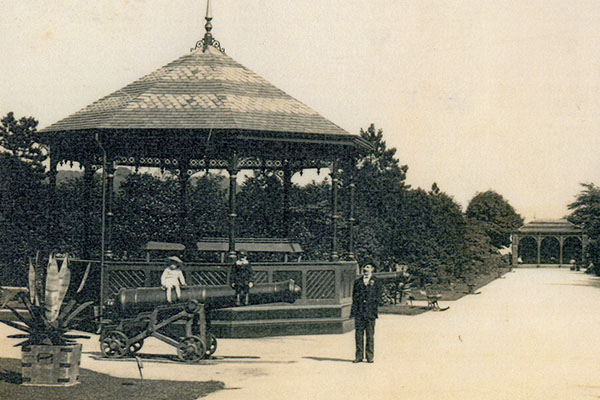

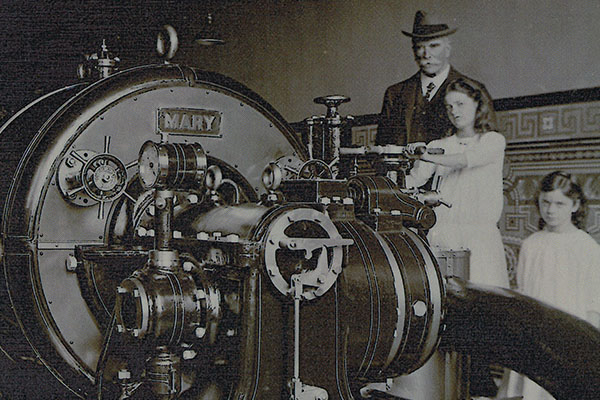

Titus decided to create a whole new industrial site away from the city. He not only built one of the largest mills in the world at the time, but also a whole model village, a community of houses, shops and public buildings for his workforce and their families.

Read on to find out how, and perhaps why, he did this.