Discover the fascinating story of Saltaire

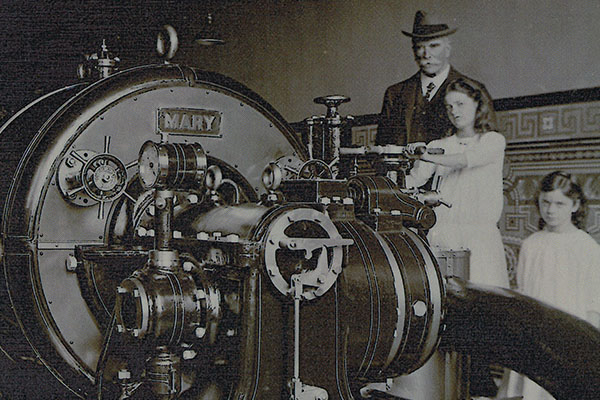

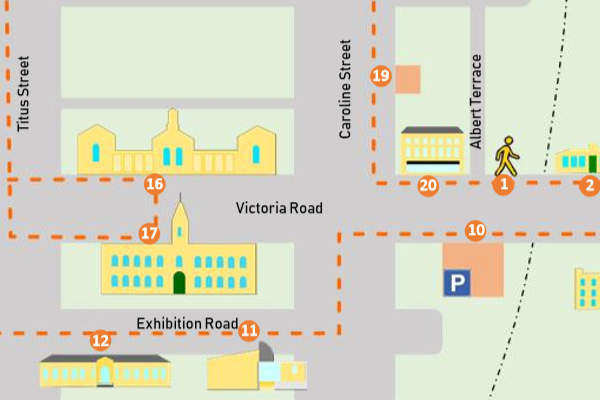

Our Collection contains a wide range of stories about Saltaire, from the middle of the nineteenth century until today.

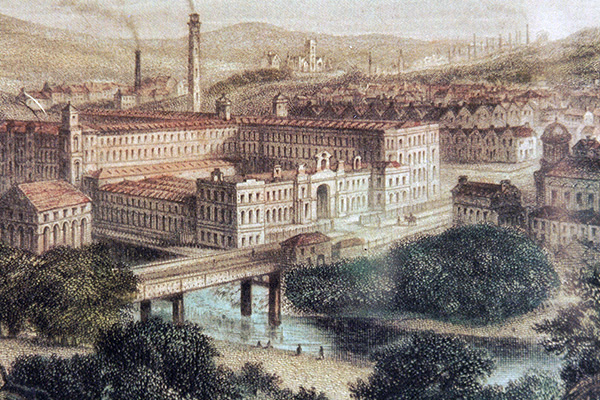

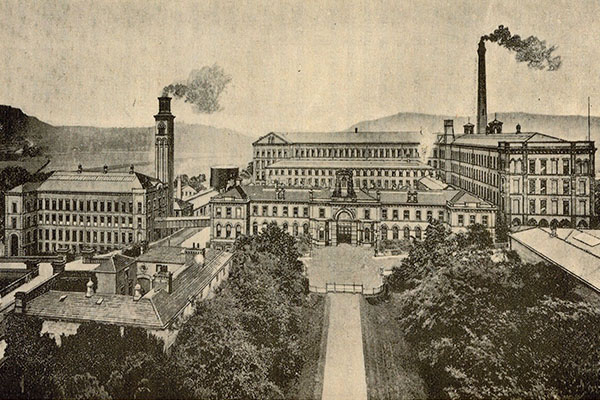

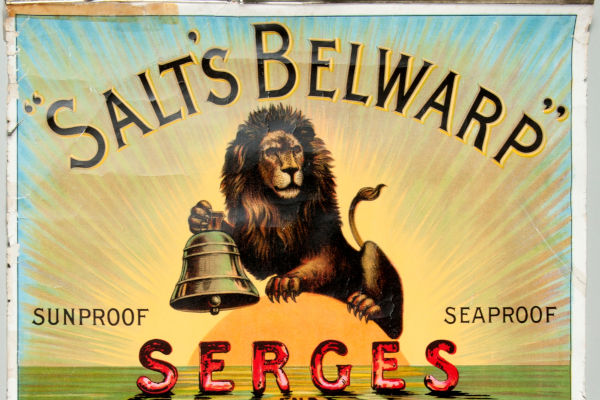

Find out why Sir Titus Salt chose to build a new mill and model village (with an amazing range of public buildings) away from overcrowded Bradford, and how Sir James Roberts built on those foundations.

Find out also about the mill workers, the residents of the village and their education and leisure interests.